British Airways, easyJet and other major carriers state that by supporting forest conservation projects they can offset emissions. A new investigation shows the bold claims can’t be verified

Britaldo Silveira Soares Filho was on a boat on Brazil’s Rio Negro river the first time he was asked to help rubber-stamp a carbon offsetting project.

The professor and expert in deforestation modelling spent three days on the boat in 2007 — along with an array of other academics focused on the Amazon rainforest — tasked by a Brazilian NGO with examining the science behind a forest conservation programme.

Later, in an office in São Paulo, he decided he didn’t want his world-leading software used for the project or others like it. To this day airlines hope backing these schemes will help them hit climate targets.

“It’s a scam,” he said. “Neither planting trees nor avoiding deforestation will make a flight carbon neutral.”

Fossil fuels have long been the cheapest and most efficient way to fuel planes, and sustainable fuels that can be used at scale are still a long way off. But the aviation sector, which has pledged to cut emissions in half by 2050, while still allowing more and more people to fly, desperately needs to find ways to reduce its carbon footprint quickly. Increasingly airlines are turning to offset programmes to help achieve this — including reduced deforestation projects where companies buy carbon credits from projects that promise to preserve forests.

“It’s a scam. Neither planting trees nor avoiding deforestation will make a flight carbon neutral.”

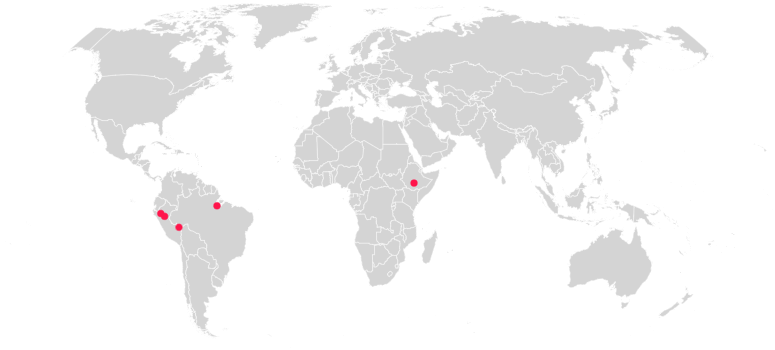

Last year, British Airways announced that its passengers could “fly carbon neutral” by buying credits for protection schemes in threatened forests. EasyJet relies on offsetting projects in Peru and Ethiopia as part of its drive to “become a more carbon neutral airline” and Delta, one of the world’s biggest airlines, uses avoided deforestation projects to support its claim that it is set to become the “first carbon neutral airline globally”. Air France, Iberia, Qantas and United Airlines have all unveiled similar programmes designed to offset passenger emissions through protecting forests.

But a detailed examination of how these schemes calculate their carbon savings by SourceMaterial, with Unearthed and the Guardian, has found evidence that raises serious doubts about the ability of these projects to offset emissions in line with the claims of major airlines. The investigation also suggests that the current flagship system for offsetting emissions through avoided deforestation may not be fit for purpose.

We analysed 10 reduced deforestation offsetting projects relied on by major airlines as part of their emissions reduction pledges and certified by Verra, the biggest issuer of carbon credits in the world. We conducted satellite analysis of deforestation in and around projects backed by BA, easyJet, and United Airlines, examined project documentation, interviewed multiple leading experts, and commissioned on-the-ground reporting.

The investigation revealed that, although projects often provide benefits to the environment and local communities, attempts to quantify, commodify and market the resulting carbon savings as a “carbon offset” are based on shaky foundations.

We found that despite multiple audits the reduced deforestation offsetting schemes used to justify eye-catching promises of carbon neutrality and guilt-free flying cannot prove they have produced enough carbon savings to justify these bold claims.

Avoided deforestation schemes generate and sell carbon credits based on the amount of deforestation they claim to prevent. In order to work out these carbon savings, they try to predict how much deforestation would take place if the project didn’t exist. Although the scenario is hypothetical, offsetting schemes use deforestation rates in comparable areas of nearby forest, so-called reference regions, to come up with an estimate.

The key findings that emerged from the investigation:

- Satellite analysis of tree cover loss in the projects’ reference regions, carried out by leading consultancy McKenzie Intelligence Services, found no evidence of deforestation in line with what had been predicted by the schemes.

- The analysis of schemes backed by BA, easyJet and United suggest the scale of the carbon benefits they offer is impossible to verify and may be exaggerated.

- The offsetting market may not be fit for purpose because projects calculate their climate benefit using what some experts viewed as simplistic methodologies that fail to account for the impact of markets and governments on deforestation.

- One environmental expert whose deforestation modelling software was used by many projects said flawed methodologies could generate “phantom credits” that represent “no impact on the climate whatsoever”.

- Discussing a project backed by BA, a government official responsible for reduced deforestation projects in Peru called the calculations behind offsetting schemes a “Pandora’s box” and “arbitrary”.

- Projects are only set to last a short period of time, sometimes only a couple of decades, meaning that the carbon savings claimed by airlines for forest preservation are not guaranteed over the longer term.

- One of the projects is run by two logging companies that cut down ancient and rare trees.

“It’s a scandalous situation,” Philip Fearnside, an ecologist at the National Institute for Research in Amazonia, said of the current state of the REDD+ system. “Most of this is pure public relations.”

The findings come as the carbon offset market is reaching a crucial turning point. The UK chancellor Rishi Sunak is aiming to make London the global hub for the trade of voluntary carbon offsets and former Bank of England governor Mark Carney is leading an effort to grow the sector with a task force of organisations involved in the market.

“It’s a scandalous situation. Most of this is pure public relations.”

They also come as Verra, the largest issuer of avoided deforestation credits, is overhauling its methodologies to help the market scale-up and following repeated media stories about the validity of the credits it produces.

In a statement, Verra said that SourceMaterial, Unearthed and the Guardian did not understand how its methodologies work, that the investigation was “fatally flawed” and had not produced fact-based journalism, ignoring their success at preserving forests.

A guessing game

Protecting forests is crucial if the world is to avoid catastrophic climate change and carbon offsets are intended to offer a mechanism to achieve this.

Since at least 2005, the UN has been discussing the idea of paying to protect forests. The idea was formalised in a collection of policies known as Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD), later REDD+, to fund conservation projects in developing countries, with the goal of mitigating climate change. The first REDD+ project began issuing carbon credits in 2011.

There is no central body to regulate these projects and carbon offset markets, meaning various companies have carved out a niche issuing carbon credits and certifying standards. These include Verra, the certifier of all the projects analysed in this investigation. It has certified nearly 1,700 projects around the globe, including projects that prevent deforestation. Today if a company needs to cut its emissions quickly, it can buy offsets from a Verra-certified project that stops trees from being cut down in an area of threatened forest.

A project has to go through a series of checks before it gets certified, to show that it will help conserve an area that faces a real threat of deforestation. Crucially, it needs to prove “additionality” — that the trees would not have been saved if the project had not existed.

To do this, a project calculates a baseline scenario of deforestation it predicts would happen if it didn’t exist. This is the yardstick a project measures itself against and the basis on which it generates carbon credits for preventing deforestation. The higher the baseline, the more credits a project can issue.

But the way baselines are calculated makes it possible for projects to overestimate their climate benefit by miscalculating the level of deforestation that would occur if they didn’t exist.

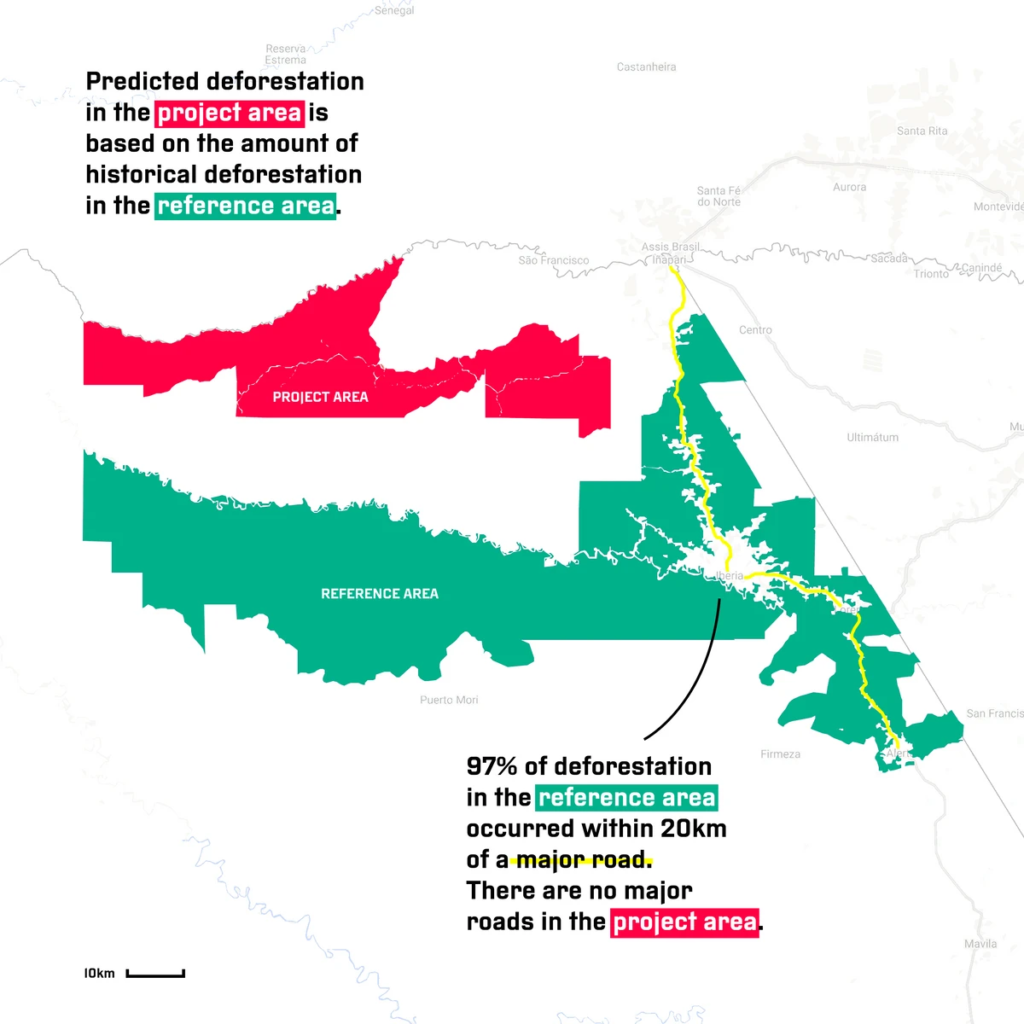

To come up with a baseline a project identifies a “reference region”, which is usually an area of forest near the project with similar characteristics. Projects use estimates of deforestation in this region — sometimes along with specific threats to the project area itself such as a new road or population growth — to assess the threat of deforestation in the project area itself.

The decision of which region to choose introduces further complications. An offsetting project supported by easyJet in a remote area of forest in the Madre de Dios region in Peru, for example, used a much more heavily populated area as a reference region, meaning its deforestation potential was much higher.

Importantly, reference regions are not intended as a control — a way of validating how much deforestation would have taken place in the real world without the project. That means there is no way to check if deforestation would have fallen without the project, due to factors beyond the project’s control. The carbon savings sold to consumers by airlines are defined by models that are not tested against reality. It’s a situation that concerns some scientists and experts.

Verra does not accept these concerns but is adapting its methods. The US-based not-for-profit is planning significant changes to baselines. Instead of choosing reference regions, historic and future deforestation will be calculated at the national level before being broken down locally. Projections of future deforestation will be based on past deforestation in that region, removing the possibility to pick and choose their reference regions. Verra also says baselines will be based only on recent deforestation and will be reviewed every four to six years.

But gaps remain. Credits will still be issued to projects for avoiding deforestation regardless of major changes in national policy; projects can issue credits even if deforestation in the country they are based in continues to rise; there is no guarantee forests will not be cut down in future after projects — some of which are only scheduled to last 20 years — end and, crucially, there remains no way of verifying if projects’ claims for their impact, based on historical models, are accurate in the real world.

The changes will also only apply going forwards. The credits sold by airlines today, and in the past, won’t be affected.

Alexandra Morel, an ecosystem scientist at the University of Dundee, told us that it’s difficult to judge if the emissions reductions claimed by REDD+ projects are real.

“It’s impossible to prove a counterfactual,” she said. “Rather than just valuing what forests are actually there, which are actively providing a carbon sink or store right now, we have to surmise which forests would still be here versus which ones are the bonus forests that were spared from the theoretical axe. It is so abstract.”

“The Verra methodologies are not robust enough,” said Thales West, who previously worked for five years as an auditor of REDD+ schemes. “That means there is room for projects to generate credits that have no impact on the climate whatsoever.”

“It’s impossible to prove a counterfactual… It is so abstract.”

West, a scientist at the New Zealand Forest Research Institute, said that Verra generates many carbon credits from projects where the benefit is much easier to quantify, such as those related to renewable energy use and reforestation, or tree-planting. “The problems come with these REDD+ methodologies,” he said, “where you simulate these deforestation baselines because there’s no perfect way to create those.”

The changes, West said, “will likely make the problem smaller, but the problem will still be there”. He pointed out that using historical rates to predict the future means changes in the wider world, like fluctuations in agricultural prices or shifting government policies, will be ignored.

West was the lead author of a study published in September 2020, which looked at 12 projects offering carbon credits for avoiding deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. The research found that the schemes had been too simplistic in drawing up their baselines.

By focusing on average historic deforestation rates, the projects had failed to account for the impact of government policies introduced in the mid-2000s — long before President Jair Bolsonaro took office — which reduced deforestation. “We find no significant evidence that voluntary REDD+ projects in the Brazilian Amazon have mitigated forest loss,” the study concluded.

One of the projects the study examined was the Floresta de Portel REDD+ project in Pará, northern Brazil, which is part of Air France’s commitment to offset all the emissions from its domestic flights. West’s study found that despite claims the project was protecting the area from devastating deforestation levels, it had very similar deforestation levels to an unprotected control area West identified nearby.

Since this study, under the presidency of Jair Bolsonaro, deforestation levels have shot up in Brazil. But even if this now means some of the predictions of forest loss by REDD+ projects in Brazil have come true, it does not vindicate Verra’s methodologies, said West.

“It’s not ideal to rely on luck to generate carbon credits. You want to rely on a methodology that is robust enough, so it doesn’t have to rely on perfect conditions.”

“It’s not ideal to rely on luck to generate carbon credits.”

When asked to comment on its support for the Portel project, an Air France spokesperson said carbon offsetting is “part of a larger scheme to address our GHG emissions”. Michael Greene, a spokesperson for the Floresta de Portel project, said the project had acted as a bulwark against the impacts of illegal loggers and cattle ranchers, noting how deforestation was now increasing again.

Modelling carbon savings

To try to predict deforestation more accurately, Verra currently permits projects to use a piece of software called Dinamica EGO. This allows users to forecast land-use changes over time and was developed by Soares Filho. We found 13 projects that cited Dinamica EGO when discussing how they designed their projects.

But this software was never intended for use by REDD+ projects. Dinamica’s website features the disclaimer: “We do not support the application of deforestation modelling to fix REDD baselines for crediting purposes.”

Instead, Dinamica was designed to be used to monitor the potential impact of specific policy decisions, said Soares Filho. In 2006, for example, he and his colleagues used it to model the devastating impact the expansion of the cattle and soy industries could have in the Amazon basin. What the software can’t do, Soares Filho said, is make a definitive estimate about future forest loss in a given area, due to all the different factors that come into play.

Soares Filho said: “Models are used to avert an undesirable future, not predict the future. Models are not crystal balls. Models are a sign to help devise policy and evaluate policy choices.”

Farm Africa, the charity that manages one of the projects backed by easyJet that used Dinamica EGO, said in response to our story: “We remain confident that the deforestation scenarios the model produced are the best that science could provide at that time.” They also stated that they were not aware of Dinamica’s online disclaimer and were not sure if it was present on the website when the analysis was conducted in 2013.

For Soares Filho, the issue goes beyond the use of one model. “Aviation companies buying REDD+ credits are just postponing action,” he told SourceMaterial and the Guardian. “It would be more efficient investing in research on more efficient jets or alternative fuels, for example. But of course, it is always more expensive than a REDD+ project.”

“Deforestation modelling to fix REDD+ baselines results in phantom carbon credits,” he added.

‘Fly carbon neutral’

The projects used by airlines are subject to multiple audits and checks by Verra and independent third parties. But we have learned that projects do not have to check whether their predictions about the threat of deforestation, which form the basis of all carbon credits issued, turn out to be true, because there is no control region.

To get an indication of whether or not the projects’ future deforestation forecasts had come to pass, Unearthed and the Guardian commissioned a new satellite analysis. Of the 10 schemes that we examined, four, backed by BA, easyJet and United, had made deforestation projections about a surrounding reference region that could be easily examined.

If tree cover loss turns out to be lower in those areas it could indicate that the original projections had been inaccurate — meaning more credits were issued than should have been.

The comparison is not perfect. Reference regions are often right next to or surrounding projects and so can be influenced either positively or negatively by what takes place in the project area. There is also the difficulty of comparing reality with an imagined scenario. However, the predictions projects make for deforestation in these areas provide the only data available to analyse the impact of these schemes and the strength of the carbon accounting compared to what actually happened.

For the analysis, McKenzie Intelligence Services (MIS), a London-based company that specialises in geospatial imagery analysis and intelligence, used annual tree cover loss data developed by Dr Matt Hansen at the University of Maryland, in collaboration with researchers from Google, the US Geological Survey and NASA.

The approach has limitations. Most significantly the satellite analysis has not been backed up by on the ground checks, meaning it’s estimates of deforestation can be inaccurate. This type of data also involves “year-to-year uncertainties” described by Global Forest Watch, an organisation that hosts Hansen’s data on its website. To ensure the analysis was as robust as possible, we used overall or average figures.

The findings were stark. The analysis found no evidence that the predicted levels of deforestation materialised in the reference regions of projects supported by BA, easyJet, and United.

The organisations behind each project claimed that the reason predictions of severe forest loss had not come to pass was because of their positive impact on reducing deforestation in their surrounding areas.

“Additionality is incredibly hard to prove,” said Crystal Davis, the director of Global Forest Watch. “While I don’t think your analysis proves by any means that the project baselines were over-inflated, it does demonstrate that post-facto assessments of the integrity of baselines is really hard to do. That’s a big problem.”

She added: “I’m encouraged to see major efforts underway to create even more public-facing transparency and accountability around REDD+ crediting.”

‘Real life Paddington’

Our analysis of two projects in Peru reveals some of the difficulties inherent in trying to prove the climate benefit of offsetting schemes.

EasyJet supports a project that claims to protect a remote area of forest in the Madre de Dios region of the country. But the reference region used to assess the threat of deforestation is a much more heavily populated area, encompassing the city of Iberia. At the time this reference region was analysed, it was split in two by an unpaved road, which has since become a major highway, connecting Peru and Brazil. MIS found that deforestation in this area was mostly concentrated around the highway and settlements, barely penetrating into the deeper jungle that more closely resembles the Madre de Dios project area.

Asked to comment on the findings of this investigation, an easyJet spokesperson told us the airline “employs a rigorous process to select the schemes we buy credits from”. Hundreds of miles north of Madre de Dios, in central Peru, the Cordillera Azul national park is home to several threatened species, including the spectacled bear, otherwise known as the “real life Paddington”. The project has become central to British Airways’ claim that passengers can “fly carbon neutral” by offsetting their flight.

CIMA, the NGO behind the project, focused on population growth when estimating potential deforestation. It argued that without additional resources as a REDD+ project, immigrants moving into the surrounding area would cut down trees in order to farm the land, predicting a huge increase in deforestation.

But the area was already a national park that had enjoyed protected status for seven years by 2008 when it started claiming credits. CIMA wrote in 2012 that “no illegal logging activities have been observed by park guards in or immediately around the project area since 2006”.

Asked whether he thought Cordillera Azul would have suffered high rates of deforestation without the REDD+ project, Deyvis Huamán, a REDD+ official in Peru’s ministry for the management of protected areas, said: “No, I don’t think so. You put yourself in the worst-case scenario, mining might come in or illegal loggers, and it could be a problem.

“It’s a Pandora’s box when you do those calculations because it’s in the formulas where you can manage those numbers, and decide whether to generate more or fewer credits… it’s kind of arbitrary sometimes. You can put values on drivers of deforestation, highways, the price of gold, the price of wood. So you put a value on the strongest driver and it might exist or it might not.”

CIMA told us that, according to its understanding, the Peruvian government “is very pleased with the contributions made by the early initiatives working on protected areas in Cordillera Azul and elsewhere, as it is providing funding and has given invaluable experience for the next steps to come, as a result of the Paris agreement.”

Responding to this investigation, a BA spokesperson said the airline aims to reach net-zero by 2050, using a range of initiatives, including carbon offsetting. They added: “We work with our partners and project developers to choose the highest quality, independently verified projects and do due diligence to ensure they provide real carbon, economic, social and environmental benefits.”

Permanence

It takes thousands of years for emitted fossil fuel carbon to leave the atmosphere. A portion of the carbon produced by a flight you took yesterday will stay in the atmosphere for millennia. In the case of the kind of unplanned deforestation schemes we looked at, an area of forest needs to stay intact for many decades in order to properly offset carbon emissions.

To deal with this problem, offsetting standards bodies set minimum lengths of time for projects to last, but these vary dramatically. A hundred years is typically the time period used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, and other respected organisations, to assess the global warming potential of greenhouse gases.

None of the schemes we examined for this story — backed by BA, Delta, easyJet, Air France, United, Iberia and Qantas — had a lifespan of 100 years. Some are only scheduled to last for a couple of decades.

Iberia said in response to the findings in this story that they chose to support a Verra-certified REDD+ project “due to the information available back in 2019 and the due diligence assessments carried out.” The airline said it was “working on updating” its offsetting program in light of the pandemic. Qantas did not respond to a request for comment.

When asked by SourceMaterial about the risks of their project areas being deforested before carbon had been properly sequestered, some schemes said that their projects would be renewed if a threat to the project area still existed at the end of its life.

Others pointed to agreements with governments to keep projects going beyond the lifespan set out in project documents at the start of the schemes.

During a project’s life, Verra forces schemes to maintain a buffer of credits —- a kind of insurance against loss of trees, for example, due to forest fires. Verra told SourceMaterial that when a project comes to an end all remaining credits in a buffer are automatically cancelled to offset future losses. In addition, Verra argues, the work of REDD+ schemes, like shifting communities away from destructive farming practices, means that the benefits brought by these projects last longer than any projects crediting period. But it admitted it does not check if this actually happens.

Verra has disputed the independence of the investigation and described it as a “hit piece” due to Greenpeace’s opposition to carbon credits, adding that many of the criticisms were now outdated that did not reflect what was currently happening with REDD+ carbon credits.

Paris agreement

Recent global treaties on climate change have given increased urgency and importance to the issue of how robust offsetting projects are. Governments are increasingly considering actions to reduce deforestation, in part because, under the Paris climate agreement, countries can include reducing deforestation in their emissions reductions plans.

We understand from sources that Norway, the world’s biggest financial supporter of forest conservation, believes national level projects deliver more significant and meaningful reductions in deforestation than voluntary schemes. The country has entered bilateral agreements with governments in several tropical countries, including Indonesia and Gabon, providing financial incentives to reduce forest loss.

Governments are able to take a more holistic approach to forest protection, Frances Seymour, distinguished senior fellow at the World Resources Institute, told SourceMaterial. Airlines and other polluters should purchase credits from regional or national governments, rather than individual projects, to reduce deforestation, she said.

“Stopping deforestation requires actions that only governments can perform: clarifying land tenure, enforcing the law, regulating permits, and rewarding conservation through tax and credit policies,” Seymour explained. “Individual projects can address local drivers of forest loss at local scale, but not economy-wide drivers at large scale.”

While Verra’s proposed changes would mean projects were integrated into national “baseline” predictions of deforestation, they will still issue credits themselves. The risk remains that consumers could pay airlines to achieve reductions in deforestation that are actually the result of global economics or government policy rather than the work of the projects themselves.

“Stopping deforestation requires actions that only governments can perform.”

Cordillera Azul is one of a number of projects that may have to adjust its baseline to match more conservative estimates from Peru’s government. “With Cordillera Azul’s methodology you say, I can verify 1.5 million credits per year,” noted Huamán, from Peru’s ministry for the management of protected areas. “But the [new post-Paris] national reference level says in that same area you can only generate 100-200 thousand credits.”

Important conservation work

Many of the schemes we’ve looked at during the course of the investigation are doing important and often difficult work, conserving forests and ecosystems. Some of the environmentalists we have spoken to for this story see REDD+ as a way of funding conservation work in dangerous parts of the world. In the absence of support from governments and other organisations, offsetting has filled a gap.

But even when projects appear to be doing good work, there can be complications. The Madre de Dios project, backed by easyJet, is in the unusual position of being run by two logging companies.

These companies, Maderacre and Maderyja, are certified by the Forest Stewardship Council and insist that they operate in a sustainable way that goes beyond requirements set by the Peruvian authorities. They argue that sustainable logging of this type can increase carbon absorption by promoting tree regeneration.

But while this type of forestry management protects younger trees as they grow, figures from Peru’s forest inspections agency show that the loggers have cut down old trees, which serve a crucial role for ecosystems, including carbon-rich shihuahuaco trees and rare species like Spanish cedar and mahogany that both appear on the IUCN red list, listed as “vulnerable”.

Julia Urrunaga, director of Peru programmes at the Environmental Investigation Agency said “it’s absurd” that a logging company should get paid for carbon credits while it cuts down old shihuahuaco trees that can take 1,000 years to reach full maturity. The project developers say they follow international rules on endangered species.

Like many REDD+ schemes, the Madre de Dios project also says it supports local Indigenous communities, who themselves often play a crucial role in sustainably using and defending forested land in their territories. But SourceMaterial has seen minutes from a meeting showing that the companies behind the scheme opposed a government proposal to expand an Indigenous reserve bordering the project area in 2017. The government was concerned that the isolated Mashco Piro tribe were being threatened by encroachment from outsiders. A representative from the Madre de Dios project argued that existing reserves were “more than sufficient” and logging concessions were a “productive conservation model”.

Project developer Greenoxx told SourceMaterial that it would welcome any decision by the authorities regarding the location of the Indigenous reserve, and noted it did not have any formal power over the decision. The NGO also highlighted its work with Indigenous communities living near the project area, claiming: “Our project is effectively contributing to the protection of their territory.”

A ‘fig leaf’ for big companies

With the global offsetting market set to take off in the coming years, Barbara Haya, a research fellow at the University of California, Berkeley who focuses on climate mitigation, told us: “Airlines and other polluters need to be more careful in how they market their support for these projects to customers and they need to have a better understanding of the climate impact of the projects they support, before making big claims.”

“It’s great if companies want to support conservation projects if these actually have positive impacts,” Gilles Dufrasne from Carbon Market Watch told SourceMaterial. “But they shouldn’t say that this compensates for their own emissions. It simply doesn’t.”

Alexandra Morel said that the current voluntary REDD+ set up places too much emphasis on scrutinising the claims of projects in poorer countries and not enough on polluters. She said the voluntary REDD+ system “relies on a level of scrutiny that puts the onus on the most vulnerable to dramatically change their lives, while the offsets go to us who are so unwilling to change ours.”

“It’s great if companies want to support conservation projects… but they shouldn’t say that this compensates for their own emissions. It simply doesn’t.”

United Airlines’ own CEO, Scott Kirby, has called offsetting “a fig leaf for a CEO to… pretend that they’ve done the right thing for sustainability when they haven’t made one bit of difference in the real world”.

Asked why, in that case, United has supported the Alto Mayo project in Peru, a United spokesperson declined to comment directly.

Former Bank of England governor Mark Carney is leading an effort to reform and grow the offsetting sector. Verra is represented on Carney’s task force, as is easyJet. The group is currently discussing how best to expand the voluntary carbon offsetting market. Whether or not to allow projects like the ones discussed in this investigation to be part of the market in future is a key sticking point.

Also on the task force are banks and other investors, who, if the UK Chancellor Rishi Sunak gets his way, will be key players in a new, multi-billion dollar market trading carbon credits in London.

It will be vital then for these credits to represent value for money and, more importantly, value for the climate.

Additional reporting: Mitra Taj